Thursday, 19 August 1993

When the phone rang that evening I was still young and naive. By the time I hung up my youth had disappeared, seared away like a drop of water on hot skillet. It wouldn’t be long before my innocence, too, was gone.

Mary and I were watching The Simpsons, the episode where Marge’s aunt dies and leaves a videotaped will. We were in the den of my father-in-law’s house in a suburban development in Newark, Delaware. The locals say New Ark, rather adamantly, so as not to be confused with that place in New Jersey. We ended up there when we found that the house we had rented was infested with fleas. Of course we didn’t find that out until after we had moved in. We moved out, bombed the 200-year-old stone farmhouse, and moved in again only to find the fleas even hungrier than before. And now they were mad, too. That’s when we moved into Mary’s father’s two-story ranch house in Newark. Poor Biscuit had so many flea baths her skin was bright red.

We searched for a place all summer, in the morning scouring ads in the paper, in the afternoon driving to look at rentals. The weather was broiling, Delaware in August, completely beyond the capacity of the AC in Mary’s Subaru. We sweated to the serenade of the seat belt alarm that chirped a constant ding-dong, ding-dong, broken from seven hours of bouncing on a trailer behind the U-Haul.

Unable to find a decent rental we had looked for a house to buy. A broker made an appointment to show us a house just over the border in Rising Sun, Maryland. The morning of the appointment the cover story on Wilmington’s The News Journal was about a black man in Rising Sun who had been pulled out of a car and beaten to death with baseball bats on Main Street. Some white guys had seen a white girl riding in the car with him. Rising Sun is the National Headquarters of the Klu Klux Klan.

Eventually we found an affordable house, affordable if we could find someone to help us pay for it, that is. It was almost directly across the street from Mary’s father’s house in the kind of suburban development we swore we would never live in. With Mary’s sister as a silent partner we made a deal and went to contract. That’s when the phone rang.

Putting the receiver down, I turned to Mary. “That was Keith. He said they found Norman’s clothes on the beach, with money in his pockets. His car was in Tony’s driveway. They think he drowned in the ocean.”

Tony Leichter was Norman’s best friend and perfect complement. Where Norman was at best indifferent to his appearance, Tony was completely anal; you had to take off your shoes before you went into his house. The mere idea of someone eating in his car made him apopletic. His wife Pamela was even worse; whenever they went out to eat, she asked for boiling water so she could disinfect the silverware at the table. When Norman came to visit, Tony followed him around with a sponge, like Felix Unger picking up after Oscar Madison in The Odd Couple. In my mind’s eye I saw Tony trying to mop up the oil spill in his gravel driveway from beneath Norman’s battered and leaking terracotta colored Mercedes

Norman seemed to operate on another level, in a place where those things didn’t matter. Then again, this may have been a carefully calculated performance, meant to disarm or distract. With Norman you never knew for sure. But one thing was sure – I knew in my heart that Norman was gone.

That spring before we moved Norman had asked me if I would run the office while he went on sabbatical. As far as I was concerned it was just another flight of fancy, like the one about sending me to Nairobi to oversee the construction of a hospital he was going to do there. I had renewed my passport for that one. When I had asked him for work that spring, he said talk to Keith. I did, only to find out that Keith was working part time. Times were tough – fallout from Black Monday had finally burst the Hamptons Bubble.

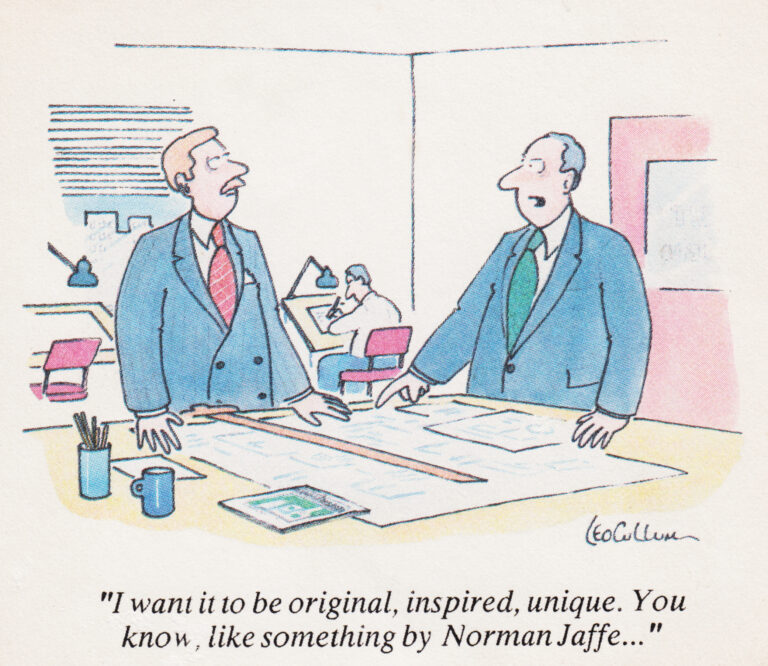

In parallel with the financial squeeze the lack of work was in part testimony to the changing times. When modern was avant-garde and an indicator of standing, Norman was able to pick and choose his clients, turning away more work than he took. By 1990 the assumption seemed to be that by having a traditionally styled house you would automatically be invested in the ‘old money ‘ social class. Never mind that the people building such houses don’t have any idea what old money actually looks – or more importantly, behaves like. In the Hamptons, where everyone is someone (‘Do you know who I am?’), they all know exactly what they want, how much it costs, and how much they are going to pay for it.

Jaffe was synonymous with modern and accordingly his designs fell out of favor. As an up and comer to the Hamptons Scene you had to have a house that looked like you inherited it from your great uncle, an English Lord.

As the latest architectural style, Postmodernism was ‘in’, too. Norman – in desperation, I think – dipped his toe in that water with a house for Mel and Chou-Chou Roslin on Dune Road in Southampton. Mel’s son Danny had been my third grade classmate at P.S. 6 in Manhattan. Danny walked by the ground-floor office we lived in on his way to school every morning, and one day he threw an egg in the window. It hit the ceiling and splattered on the floor. The next morning Norman waited in the vestibule. When Danny came by Norman leaped out, hoping to scare him, but slipped and fell on top of him, pinning him to the sidewalk. I’ll bet that scared him.

Mel Roslin was a typical Hampton’s client – too much money and not much of anything else. A manufacturer of women’s underwear, he defined himself with a one-liner about how the sixties really hurt him (‘they burned their bras’). Chou-Chou was a ridiculously overstuffed platinum blonde who later divorced him for a pile of cash.

Roslin was so cheap he squeaked when he walked; he shorted Norman the entire final contract payment, about seventy thousand dollars. Norman brought this on himself by not keeping up with the ever-rising construction cost and his percentage billing, but to have paid attention to such administrative tasks would have interfered with his act as the Great Artist. Or maybe such mundane concerns were beneath him.

A few weeks before he went for a swim, Norman called me in Delaware and raised the sabbatical issue again. I was in summer school, a programming class, boning up for a graduate program in computer science and in theory preparing for my next life. Then he surprised me.

“I have this terrible health problem,” he said, “it’s debilitating.” His voice was strained. He refused to elaborate, as if he had inadvertently disclosed a secret. When I pushed him for more he ended the conversation quickly.

Concerned, I sent him a letter. ‘When you broke your leg, there were things I could do to help. You have to tell me what’s wrong so I can help you now.’

A week later Norman called again. “It was just insomnia,” he said, shrugging off my concern. “Why don’t you come up for a couple of weeks and stay at the house with me? Sarah’s not here, it’ll be just like old times.”

How I wish I hadn’t declined. It all makes sense now. What a funny thing to say about your father’s suicide.